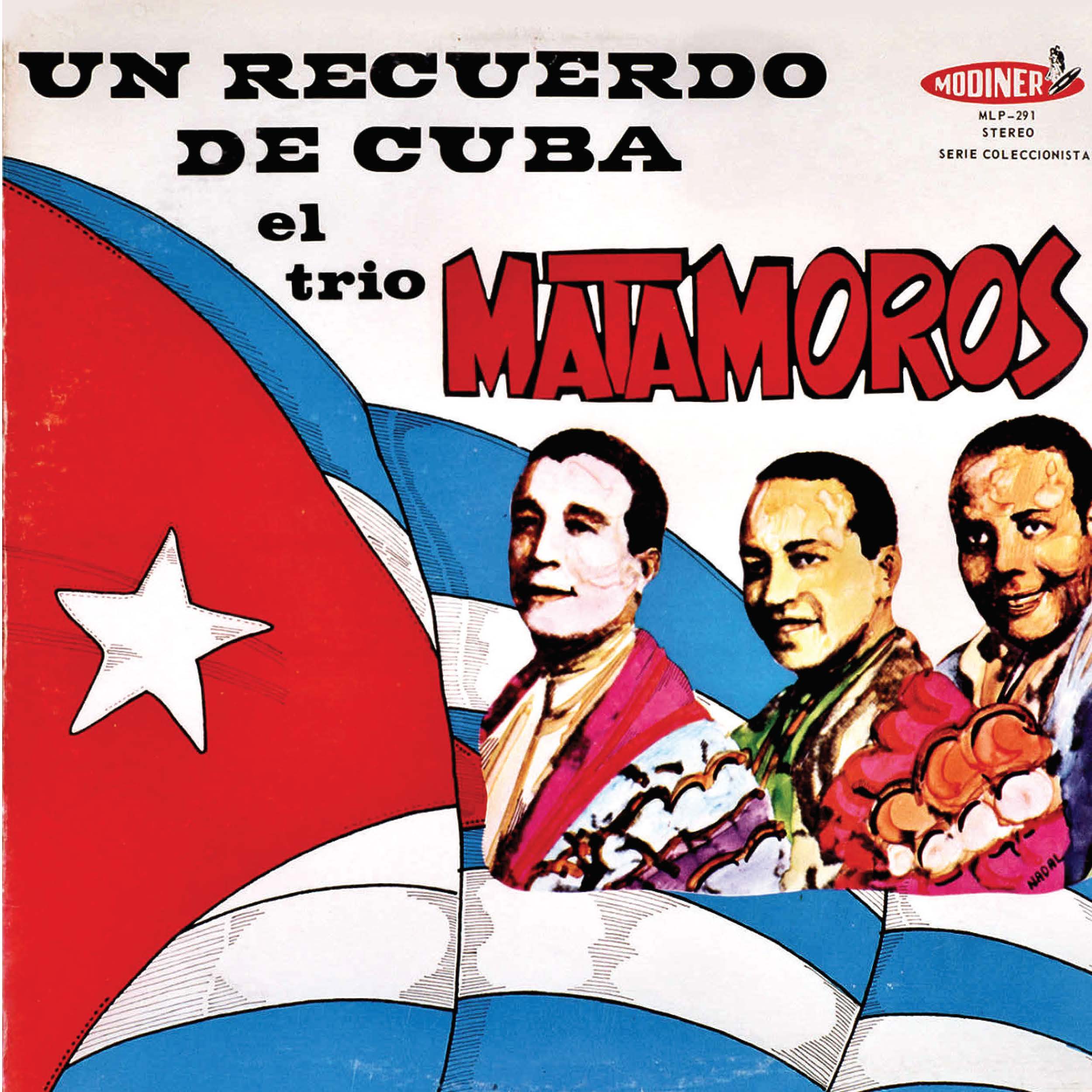

¿Cuándo llegará la Nochebuena? That was my Grandmother Mercedes’s favorite song. The Trío Matamoros interpretation. I will never forget the preparations for Christmas Eve, especially in guajiro households, in the countryside, a place where December 24 earned its greatest splendor. To prepare the hayacas—what the habaneros called tamales—each one of us had our task. My cousin Nenena peeled the corn; Tanya, my other cousin, milling the grain. Aunt Fefa put small pieces of pork into the masa harina, wrapping the dough in the husks. At another station, Ely cut the lettuce, avocados and tomatoes, while Puchita prepared an immense mixed salad. In the coal and wood stove, my mother prepared huge pots of congri—rice and beans—sweet potato, cassava and yam. Uncle Nene was called on to give a tremendous janazo to the head of the poor pig he had fed like a king for thirty days in anticipation of this date. In an instant, the revelry gave way to moments of cruelty. In his last sighs that pig began to squeal, while my cousins Gallego, Nenecito and I, dead scared, held down the legs. Suddenly, the expert hands of Uncle Nene stab at the jugular. With that moment, the uproar resumed: the suckling danced on a prong and into the bonfire they threw spears of guava. In the courtyard, a cloud of smoke slowly penetrating into the mass of piglet and filling bathed in a delicious aroma and unforgettable taste. Then someone turns up the radio volume a todo dar, to let the whole neighborhood hear the music of the Matamoros Trio, the Ignacio Piñeyro Septet, of Chapotín, Abelardo Barroso, and Chepín and his Orquesta Oriental. Into the night we sat on stools of leather around a long table. We were always more than thirty people. And so commenced the best part of Nochebuena, between dances and songs, casabe, Spanish nougats, cider, soft drinks, Pru Oriental, brandy, casseroles of food brought from the kitchen, and that giant roast suckling pig, which, I swore, did not stop watching me.

— Iván Acosta

¿Cuándo llegará la Nochebuena? Esa era la canción preferida de mi abuela Mercedes. La interpretaba El Trío Matamoros. Nunca olvidaré los preparativos de Nochebuena, especialmente en los hogares guajiros, en la campiña, lugar donde el 24 de diciembre cobraba su mayor esplendor. Para preparar las hayacas—lo que los habaneros llaman tamales—cada cual tenía su tarea. Mi prima Nenena pelaba el maíz; Tanya, mi otra prima, molía el grano. Tía Fefa le ponía trocitos de puerco a la harina según iba envolviendo la masa en las mismas hojas de maíz. Por otro lado, Ely cortaba lechuga, el aguacate y los tomates, mientras Puchita preparaba una inmensa ensalada mixta. En el fogón de carbón y madera, mi mamá preparaba enormes cazuelas de congrí, boniato, yuca y ñame. A mi tío Nené le tocaba darle un tremendo janazo por la cabeza al pobre cerdo que él había alimentado a cuerpo de rey durante los últimos 30 días en anticipación de esta fecha. Por unos instantes, el jolgorio daba paso a momentos de crueldad. El cochino aquel en sus últimos suspiros empezaba a chillar, mientras mis primos Gallego, Nenecito y yo, muertos de miedo, le sujetábamos las patas. De pronto, de la mano experta del tío Nené, la puñalada en la yugular. A partir de ese momento, resumía la algarabía: el lechón bailaba en la púa y a la hoguera se arrojaban gajos de guayaba. En el patio se levantaba una humarada que lentamente penetraba en la masa del lechón y del relleno, que se impregnaban de un delicioso aroma y de un sabor inolvidable. Entonces alguien subía el volumen del radio a todo dar para que el vecindario entero escuchara la música de los Matamoros, del Septeto de Ignacio Piñeyro, de Chapotín, Abelardo Barroso, y Chepín y su Orquesta Oriental. Entrada la noche nos sentábamos en taburetes de cuero alrededor de una larguísima mesa. Siempre éramos más que 30 personas. Y comenzaba la mejor parte de la Nochebuena, entre bailes y cantos, casabe, turrones españoles, sidra, refrescos, Pru oriental, aguardiente, las cazuelas de comida que se traían de la cocina, y aquel gigantesco lechón asado que, yo hubiera jurado, no dejaba de mirarme.

— Iván Acosta

Iván Acosta

Not a novel of politics, not a history of Cuban music, not an autobiography, but an anecdotal and musical journey of a soul, “a Cuban, an exile, a Cuban-American” liberated by and with the music. A double album compilation on Un-Gyve Records and an exhibition of the album artwork coincides with the publication of With a Cuban song in the heart which includes both the English and Spanish versions of the text. Introduced by Marc Myers.